For polar bears across the Arctic, the arrival of fall presages a coming bounty, as waters begin to freeze, sea ice begins to form, and bears prepare themselves for a winter hunting on the ice.

In some parts of the polar bears’ range, such as the islands of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, ice persists through the summer. But elsewhere, fall’s return prompts an uptick in activity as the bears anticipate the largely ice-free summer months finally giving way to an icy smorgasbord.

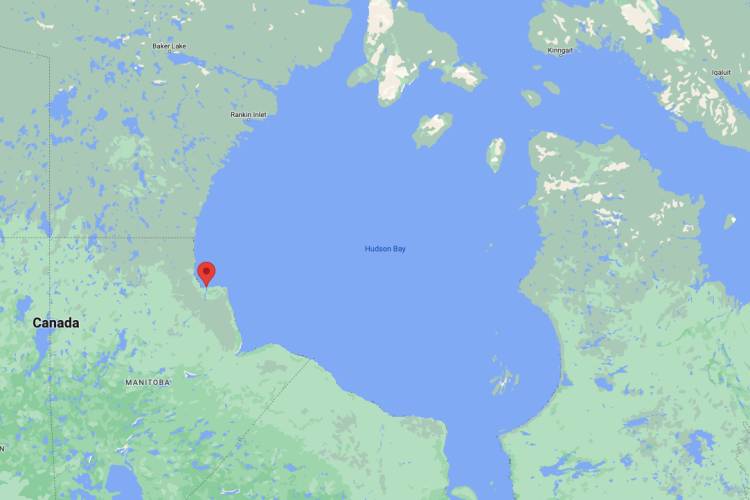

With 20 populations of polar bears across the Arctic, there are 20 different stories as the bears adjust to different ice conditions. Following are some representative populations.

Norway’s Svalbard archipelago

In the Barents Sea, the bulk of the population spends as much of the year as possible on drifting sea ice, while a smaller number of bears – roughly 250 – remain on the coastal ice around Svalbard. During fall, says Jon Aars, senior scientist with the Norwegian Polar Institute, "The coastal bears have no choice, they have to stay on land, as there is no sea ice in most places on Svalbard from September until late in the fall.” Even when the ice does begin to form, these coastal bears remain close to shore at all times.

In the Svalbard region, sea ice is constantly being pushed away from shore by currents, and so, when summer arrives and new ice is no longer being formed, some of the so-called pelagic bears may find themselves trapped on or near land as the sea ice drifts away; come fall, they will be waiting anxiously for the ice to re-form so they can once more set out far from shore. Others, however, never leave the ice at all if they can avoid it.

“You can have pelagic bears in Svalbard or the Barents Sea that are on the ice 12 months a year,” explains Aars.